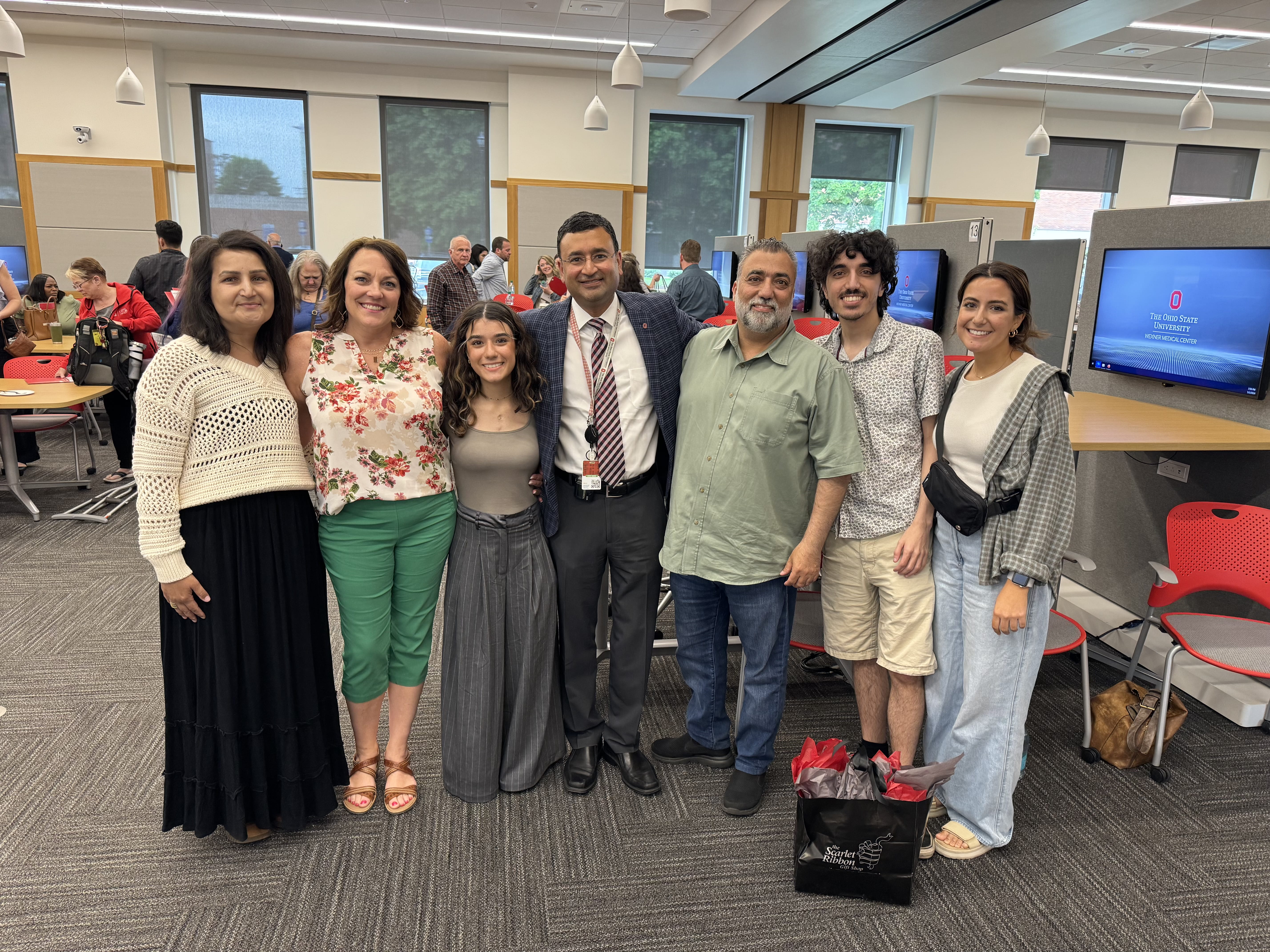

Gigi Humeidan and her family at the ECMO Symposium Friday at the Wexner Medical Center. From left to right: Rola Humeidan, Kelly Renee, Gigi Humeidan, Dr. Nakush Mokadom, Monjed Humeidan, Manar Humeidan and Emily Humeidan. Credit: Courtesy of Gigi Humeidan

Gigi Humeidan is one of 45,728 undergraduates at Ohio State, but her journey to this university has been unlike any other.

Humeidan, a second-year in health sciences, shared her experience with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation — also known as ECMO — at the Wexner Medical Center’s ECMO Symposium Friday. According to the Cleveland Clinic, ECMO is an artificial life support that aids a person whose lungs and heart aren’t functioning correctly.

In interviews with The Lantern, Humeidan and her heart surgeon shared more about her journey.

When Humeidan was 16 years old, she suffered from cardiac arrest while at a family gathering, according to her heart surgeon Dr. Nahush Mokadam, division director of cardiac surgery at the Wexner Medical Center. Luckily, Humeidan’s aunt is an anesthesiologist who administered CPR until Humeidan was taken to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, where she was placed on ECMO.

Humeidan said she wanted to discuss her ECMO experience with medical professionals because she loves telling her story and spreading awareness.

“It felt really good,” Humeidan said. “It felt really inspiring.”

That same year, Humeidan was transferred to the Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital and put under Mokadam’s care. Humeidan has a rare genetic condition that led her to experience these unexpected heart problems, and Mokadam said “there was no way to get her out of it.” The ECMO was too temporary of a solution — she needed a total artificial heart while she waited for a heart transplant, Mokadam said.

Since much of the ECMO and artificial heart equipment available is designed for adults, not adolescents, Humeidan encountered complications — specifically, the loss of her leg.

“When we attach people to ECMO, one of the ways we do it is to use the blood vessels in the groin,” Mokadom said. “There’s an artery and a vein in the groin. That’s a relatively large blood vessel in everybody. But again, she’s a petite woman and most of the equipment we have is geared towards larger people. And she formed a blood clot downstream of one of those tubes that we used to attach her to the ECMO circuit. And that blood clot resulted in her losing her leg.”

Mokadam said Humeidan is a role model for persevering through such difficult medical issues.

“She’s an inspiration to us all,” Mokadam said. “Not only to her family and friends, but to all her caregivers. Because she has to do the hard part of the fight. She has to learn to walk again. She has to learn how to use [a] prosthesis. She has to learn how to deal with a new body image that was different from what she was used to.”

Gigi Humeidan with her heart surgeon, Dr. Nahush Mokadom at Ross Heart Hospital. Credit: Courtesy of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Humeidan’s character and personality contributed to her remarkable resilience, Mokadam said.

“She’s upbeat,” Mokadam said. “She has a lot of spirit. She has a great positive outlook on life. She’s a delight.”

Humeidan said she recovered fairly quickly after her heart transplant and loss of her leg.

“It felt very long, but I did recover pretty fast,” Humeidan said. “It felt really good to walk with the prosthetic leg after just not being able to even stand without one. So it was just very exciting, I’d say. The recovery felt really good.”

To pay forward the help she received in the hospital, Humeidan wants to become a physical therapist after graduating from Ohio State.

“I feel like I have a really good insight towards the whole thing since I was in physical therapy for two or three years,” Humeidan said. “I feel like I could help people the way I was helped. I want to work with either amputees or pediatrics.”

The quickness with which Humeidan was able to progress in physical therapy is one of the reasons she wants to pursue the career.

“One of my first sessions was inpatient, and I wasn’t even able to move a finger or lift my head,” Humeidan said. “A couple of weeks later, I was able to do both.”

Mokadom said all doctors need patients like Humeidan now and again in their careers.

“It gives you inspiration, hope [and] reinforcement that the long hours and the hard work are worth it, and then it validates you,” Mokadom said.